I never expected to be an artist. Artists have always been people I revered for their astonishing, superhuman talents. I was a writer, that was something I could do. We all use words, after all. For as long as I can remember, I wanted to be a writer. In particular, I wanted to be a poet. And I sort of became one. I was very determined, as well as being completely in love with Sylvia Plath’s poetry and all that she represented to my romantic twenty-something soul.

I became a poet and had some minor successes. I published several ‘slim volumes’. At the time it felt wonderful, but there was also a lot of negative stuff. Sophie Hannah reviewed my work in PN Review. She described my work as ‘clumsy’, ‘cliched’, ‘tired and predictable’, ‘boring’, etc. And that hurt; of course it hurt. There was more to come. Poets Roddy Lumsden and David Kennedy were equally sneering. Lumsden referred to my poetry as ‘lurid’. Kennedy was equally disparaging. I do feel somewhat bad for singling out Lumsden and Kennedy as they are both now dead (Kennedy died in 2017, Lumsden in 2020). Lumsden did offer me a half-hearted apology in later years, but it was very much of the passive-aggressive “I’m sorry you felt hurt” variety that didn’t actually help at all.

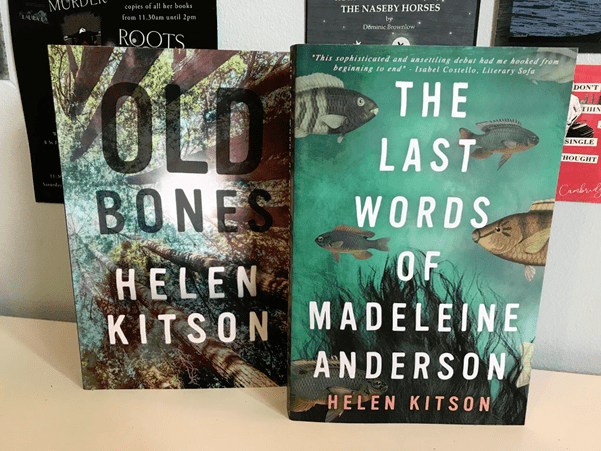

I won’t say that negative reviews made me give up writing, but they certainly didn’t inspire me to continue. I went on to publish two novels, both of which have sunk pretty much without trace, and for those I received some wholly negative reviews as well as a few glowing ones. That’s just the way it is, for most writers.

Ironically, perhaps, my writing – and certainly my poetry – has far more in common with the artwork of Tracey Emin than my artwork does. As an artist, I have no interest in politics or gritty social realism or being shocking or transgressive. Clearly I don’t have much in common with the ‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’ school of thought either, but my art is not (at least never deliberately) provocative. Perhaps, when I was younger, I was guilty of being too wedded to the ‘dirty realism’ school of poetry, but on the whole I simply used poetry to reflect the reality of my life. I used clichés for deliberate effect, but of course we can’t predict how others will read our work (more’s the pity!).

Art is, I find, far more freeing than writing. No one is obliged to purchase my work without knowing exactly what they’re getting. If they don’t like it, they move on and look for something they do like. If they do want to own a piece of my work, they do so freely, no strings attached. For a writer whose sales depended to a large extent on receiving good reviews, on being active on social media and on trying to secure the ever-elusive real life exposure, this was a game changer.

And of course it did take me a good long while to pluck up the courage to put my artwork out there. I’m a wholly self-taught artist, I can’t draw, and the work I do is quite niche, what right did I have to go calling myself an artist?

I took courage from artists I follow on Instagram, whose work I love, and who have been so kind and generous to me over the years. Just like novels, poems, and short stories, art is subjective. Sometimes it’s difficult to remember this, or to accept it, in the face of what sometimes seems like unwarranted criticism from people who just don’t get what we’re trying to do (but why should they, after all?).

*

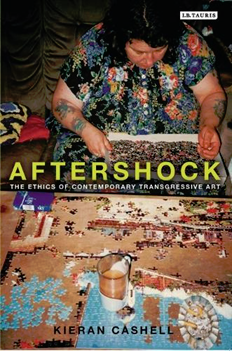

I have recently finished reading a very thought-provoking book by Kieran Cashell. Titled ‘Aftershock’, it is subtitled ‘The Ethics of Contemporary Transgressive Art’. I picked the book up in one of my favourite local charity shops, because the title sounded intriguing.

Some of the criticisms of the artworks and artists dealt with in the book remind me of the worst of the sneering, caustic reviews I received for my poetry. I don’t want to dwell any more on the latter (my life as a poet is a very long time in the past!) but I do find it interesting the way ‘transgressive’ art is viewed, and sometimes excused, and sometimes you just wonder why no one gets it because it seems so obvious.

The works dealt with in the books are, by and large, the usual suspects: Richard Billingham’s uncomfortable but compelling photographs of his parents; Marcus Harvey’s handprints painting of Myra Hindley; the Chapman Brothers (‘nuff said!); Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst.

I find Cashell’s chapter on the Chapman Brothers persuasive but not entirely convincing. The Marcus Harvey painting is, I feel, more complex and nuanced than it’s often given credit for. Billingham’s photographs make me feel uncomfortable, but I don’t think it’s possible to dismiss him as a ‘tourist’ given that the material he deals with concerns his own past, and his own family.

Tracey Emin is, of all the artists dealt with in the book, the one I most admire, perhaps because I understand her and her work the best. That she is now a Dame is really quite extraordinary and wonderful. She is, perhaps, the most noteworthy role model for screwing up your life and using those screw-ups to redeem yourself meaningfully through art. This probably also explains why I dislike Damien Hirst’s work with such a passion: what Cashell describes as ‘Sustained, speculative and clinically detached’, referring to Hirst’s ‘disinterested contemplation’ of victims of suicide, road accidents, and the like. Or perhaps that makes Hirst more honest? How many of us, after all, enjoy reading about and watching dramas about true crime? When Hirst speaks about looking at pictures of these victims of tragedy as ‘like cookery books’, perhaps he’s simply being more honest than many of us could bear to admit.

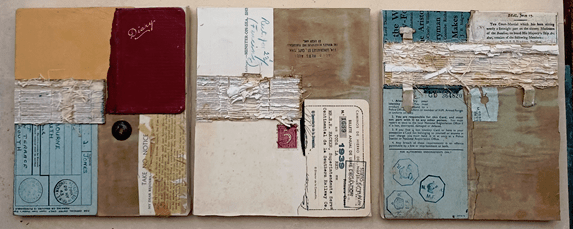

(c) Helen Kitson 2025 ‘Identities’

I’m also reading ‘Blimey’ by Matthew Collings, having enjoyed his later book ‘Art Crazy Nation’. Collings isn’t a fan of the kind of very precious, academic, two-paragraphs-to-sum-up-one-sentence kind of art school language. And to some extent I sympathise. It’s annoying and also slightly amusing to read a long-winded scholarly art history article that could, really, be summarised in a couple of short paragraphs. By way of contrast Collings adopts a gossipy, faux-naïve style, that is actually equally irritating, if not more so. Still very readable, nevertheless, although ‘Art Crazy Nation’ is by far the better, and certainly more thoughtful, book in my opinion.

But, you know, art books can be divisive and that’s good, because art itself is divisive. We all have different ideas about what constitutes ‘art’. And that is a good thing.

Leave a comment